Configuration, State, and Degrees of Freedom

Configuration and C-Space

The first question to answer in robotics is, simply, where is the robot?.

A proper complete answer would require knowing position of every single point in the robot with respect to some global frame. This complete specification is called the robot's configuration.

Configuration of a robot specifies the position of every point of the robot

A configuration, denoted by

The C-space is a crazy concept because it transforms the complex geometric problem of a robot moving among obstacles in the physical workspace into a simpler problem of a single point moving in this higher-dimensional C-space. Configurations where the robot does not collide with obstacles are part of the collision-free C-space.

Degrees of Freedom (DOF)

The number of degrees of freedom (DOF) is the minimum number of independent parameters needed to completely specify the robot's configuration.

This means the DOF is also the dimension of the robot's C-space.

- A point in a 2D plane has 2 DOF, described by

. - A rigid body in a 2D plane requires three parameters: its position

and its orientation . It therefore has 3 DOF. - A rigid body in 3D space requires six parameters: its position

and its orientation, which can be described by three angles (e.g., roll, pitch, yaw). It has 6 DOF.

We can develop an intuition for this by considering the constraints on a rigid body. In 2D, once we fix the position of a point A (2 DOF), a second point B is constrained to lie on a circle around A (1 more DOF). Any other point C is then fully determined by its distances to A and B. The total is

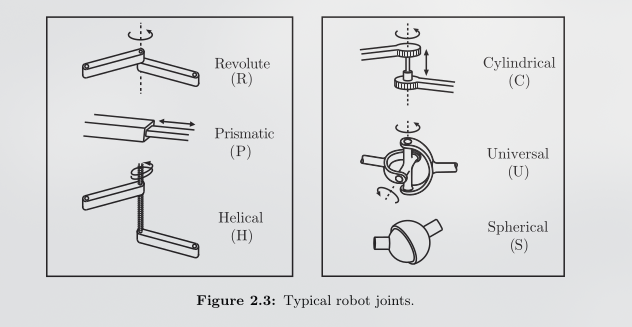

Robot Joints

Robots are typically composed of rigid bodies called links connected by joints. Joints introduce constraints and reduce the overall DOF of the system.

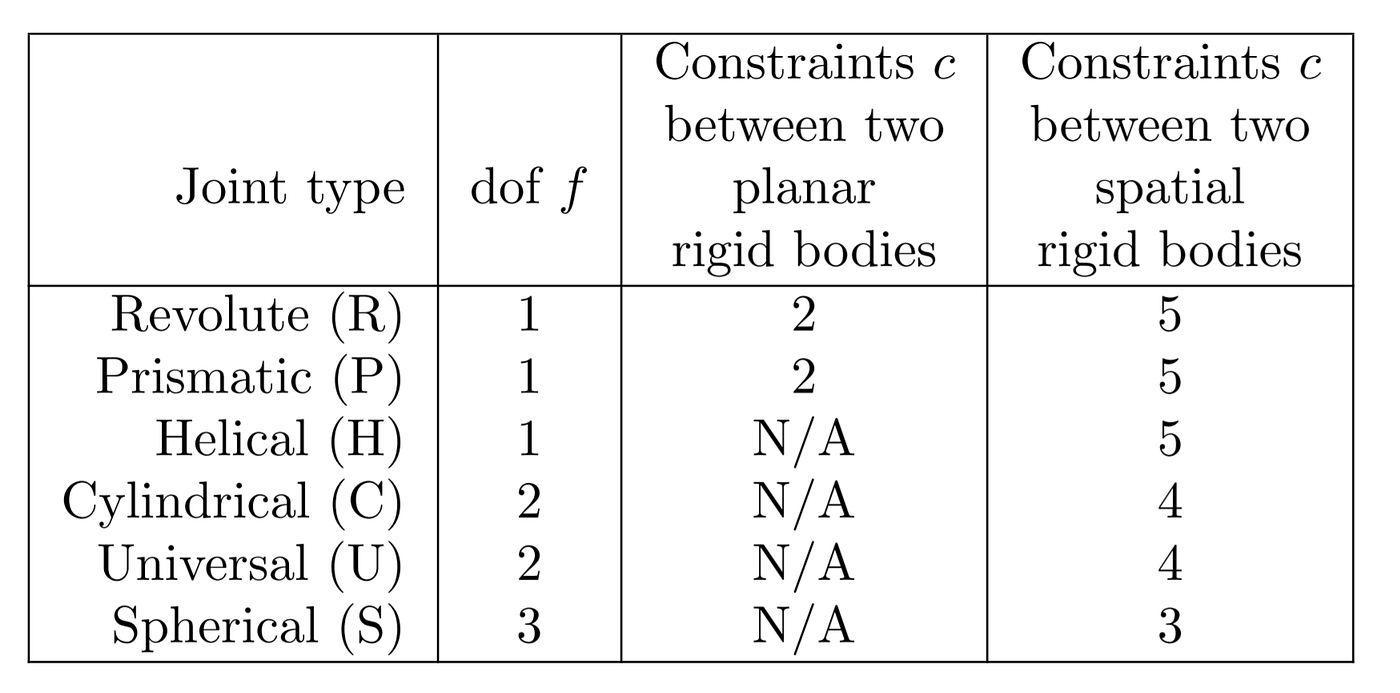

Image taken from Modern Robotics: Mechanics, Planning, and Control

Grübler's Formula

To calculate the DOF of a mechanism, we can use Grübler's Formula. This formula is based on the principle of subtracting the constraints imposed by joints from the total possible freedoms of the links.

where:

is the DOF of a single rigid body in the workspace ( for planar mechanisms, for spatial mechanisms). is the total number of links, including the fixed base (ground). is the total number of joints. is the number of freedoms provided by joint .

Example: A 3R Planar Arm

For a planar arm with three revolute joints connected in a series to a base:

- It's a planar mechanism, so

. - There are 3 moving links and 1 ground link, so

. - There are 3 revolute joints, so

. - Each planar revolute joint has 1 DOF, so

for all three joints.

Plugging this into the formula:

This confirms our intuition that the arm has 3 degrees of freedom.

Important Note: Grübler's formula is only valid if all joint constraints are independent. For some mechanisms with redundant constraints, it may yield an incorrect result.

Rigid Body Transformations in 2D

To describe a robot's configuration mathematically, we move from the notions of Euclidean geometry to the algebraic framework of Cartesian geometry. These are there in Co-ordinate-Transforms some what.

Coordinate Frames and Rotation

We attach coordinate frames to objects of interest.

A point

To describe a robot's motion, we need to relate points described in a local body frame

The derivation proceeds as follows:

- The basis vectors of

in terms of using trigonometry:

- A point vector in the body frame is

. Substitute the expressions from step 1 to find the same point vector relative to the world frame, :

- Group the

and terms:

- This can be written in matrix form, which gives us the 2D rotation matrix:

This relationship is compactly written as

The Special Orthogonal Group

Rotation matrices have several important properties:

- They are orthogonal, meaning

. Therefore - Their columns are mutually orthogonal unit vectors.

- Their determinant is always

. A rotation preserves the length of vectors and the "handedness" of the coordinate system. (_Note: Not related to SO(2) but when we have determinant -1, it represents a reflection.)

The set of all

Homogeneous Transformations and

When a frame is both rotated by

- A 2D point

becomes a 3D vector . - The transformation becomes a

matrix .

Now, the transformation is a single, clean multiplication:

These

(That's because it's a property of SE(2) that the composition of two transformations is another transformation in SE(2).)

The fundamental insight is that the columns of a rotation matrix

When we need to account for both rotation and translation, we use homogeneous coordinates. This combines the rotation matrix

Example

A point

The first rotation is by

The second rotation is by

To find the final orientation of the body, we post-multiply the first rotation by the second.

Now we can find the final coordinates

The final coordinates of the point are

Singularities in Orientation: Gimbal Lock

While representing orientation with a sequence of three rotations (Euler angles) is intuitive, it suffers from a critical problem known as gimbal lock. This is a singularity where the alignment of two rotation axes causes the loss of one degree of rotational freedom. I cover this in more detail in my EULER ANGLES note.

Let's examine the mathematical reason for this. Consider a ZYX roll-pitch-yaw convention. The final rotation is

The full rotation becomes:

A useful property of rotation matrices states that

The final orientation now depends only on the sum of the yaw and roll angles, not their individual values. We can no longer distinguish between a yaw and a roll motion; the system has become degenerate and lost a degree of freedom.

Axis-Angle Representation

An alternative, non-singular way to represent orientation is the axis-angle form. Euler's rotation theorem states that any orientation in 3D space can be described as a single rotation by an angle

Rodrigues' Formula Derivation

Rodrigues' formula provides a direct mapping from an axis

Step 1: Decompose the Vector

We want to rotate a vector

The parallel component is the projection of

The perpendicular component is what remains:

Step 2: Rotate the Components

The rotation only affects the perpendicular component. The parallel component lies on the axis of rotation and is therefore unchanged.

The component

Since

Step 3: Recombine and Simplify

The final rotated vector,

Substitute the expressions for

Grouping terms for

This is the vector form of Rodrigues' formula.

Step 4: Convert to Matrix Form

To get the matrix

The term

Substituting these into the vector formula gives the final matrix form of Rodrigues' formula:

Using the identity for